San Diego seawalls depend on Half Moon Bay case | San Diego Reader

Landmark Ruling Could Reshape California's Coastal Future: Court Sides with Commission on Seawall Restrictions

In

a decision that could reshape California's coastline, a state appeals

court has tentatively ruled that thousands of coastal homeowners may

lose their right to build protective seawalls against rising seas. The

ruling, centered on a dispute in Half Moon Bay, supports the California

Coastal Commission's position that only buildings constructed before

1977 are entitled to new seawall permits.The case began when the Casa Mira townhomes, built in 1984, lost 20 feet of protective bluffs during a 2016 storm. When the homeowners sought to construct a permanent 257-foot concrete seawall, the Coastal Commission denied their request, sparking a legal battle that has drawn attention from environmental groups, developers, and coastal communities across the state.

While a lower court initially sided with the property owners, the First District Court of Appeal in San Francisco has indicated it will uphold the Commission's more restrictive interpretation of the Coastal Act. The Commission argues that seawalls, which already armor one-third of Southern California's coastline, prevent natural beach migration and accelerate beach loss as sea levels rise. According to state projections, between $8 billion and $10 billion worth of California coastal property could be underwater by 2050.

The ruling's impact extends far beyond the ten townhomes at Casa Mira. "This is not just a California problem," says Charles Lester, director of the Ocean and Coastal Policy Center at UC Santa Barbara. "There are houses falling into the ocean in North Carolina, in Hawaii and other places. The question is what do we choose to protect over the long run? What's in the public interest?"

A final decision is expected after a December 11 hearing, though experts anticipate the case may ultimately reach the California Supreme Court. Ironically, the Casa Mira homeowners might still secure their seawall, but only because it would protect a public coastal trail rather than their private homes. The case highlights the growing tension between private property rights and public beach access as climate change threatens California's 1,100-mile coastline.

Summary of State of Play

The key legal dispute centers on Section 30235 of the California Coastal Act, which states that seawalls and other protective structures "shall be permitted" to protect "existing structures" threatened by erosion. The core issue is the interpretation of what constitutes an "existing structure."

Current status:

- - A tentative ruling by the 1st District Court of Appeal in San Francisco (October 2023) supports the California Coastal Commission's position that only buildings constructed before January 1, 1977 (when the Coastal Act took effect) are entitled to seawall permits.

Historical context:

- - For the first 38 years (1977-2015), the Coastal Commission interpreted "existing structures" to mean any building that existed at the time of a seawall permit application

- - In 2015, the Commission changed its interpretation to only include pre-1977 structures

- - This interpretation was challenged in the Casa Mira case, where property owners sued after being denied a seawall permit for townhomes built in 1984

Legal developments:

- The San Mateo County Superior Court initially ruled in favor of the property owners (Casa Mira), finding the Commission's restrictive interpretation unreasonable

- The Commission appealed, leading to the current tentative ruling favoring the Commission's position

- A final ruling is expected after a December 11, 2023 hearing

- The case may ultimately reach the California Supreme Court given its significant implications

Interestingly, the appeals court indicated that Casa Mira might still get their desired seawall, but only because it would protect the California Coastal Trail (a public access way) rather than the private structures - as protecting public access is allowed under the Coastal Act.

San Diego seawalls depend on Half Moon Bay case | San Diego Reader

In a decision that could reshape California's coastline, a state appeals court has tentatively ruled that thousands of coastal homeowners may lose their right to build protective seawalls against rising seas. The ruling, centered on a dispute in Half Moon Bay, supports the California Coastal Commission's position that only buildings constructed before 1977 are entitled to new seawall permits.

The case began when the Casa Mira townhomes, built in 1984, lost 20 feet of protective bluffs during a 2016 storm. When the homeowners sought to construct a permanent 257-foot concrete seawall, the Coastal Commission denied their request, sparking a legal battle that has drawn attention from environmental groups, developers, and coastal communities across the state.

While a lower court initially sided with the property owners, the First District Court of Appeal in San Francisco has indicated it will uphold the Commission's more restrictive interpretation of the Coastal Act. The Commission argues that seawalls, which already armor one-third of Southern California's coastline, prevent natural beach migration and accelerate beach loss as sea levels rise. According to state projections, between $8 billion and $10 billion worth of California coastal property could be underwater by 2050.

The ruling's impact extends far beyond the ten townhomes at Casa Mira. "This is not just a California problem," says Charles Lester, director of the Ocean and Coastal Policy Center at UC Santa Barbara. "There are houses falling into the ocean in North Carolina, in Hawaii and other places. The question is what do we choose to protect over the long run? What's in the public interest?"

A final decision is expected after a December 11 hearing, though experts anticipate the case may ultimately reach the California Supreme Court. Ironically, the Casa Mira homeowners might still secure their seawall, but only because it would protect a public coastal trail rather than their private homes. The case highlights the growing tension between private property rights and public beach access as climate change threatens California's 1,100-mile coastline.

Casa Mira townhomes sued after losing 20 feet of bluffs in storm

San Diego seawalls depend on Half Moon Bay case

Casa Mira townhomes sued after losing 20 feet of bluffs in storm

Del Mar Bluffs 5

A lawsuit that had beachfront property owners feeling hopeful about relying on seawalls to protect their homes is leaning the other way — upholding limits on coastal armor.

The fight between homeowners and the California Coastal Commission hinges on whether to allow for seawalls to defend any structure on the beach or only those built before the California Coastal Act took effect on Jan 1, 1977.

The case involves ten townhomes in Half Moon Bay (29 miles south of San Francisco), but could affect thousands of private properties and hundreds of public beaches from San Diego to the Oregon border.

According to a report by the Legislative Analyst's Office, between $8 billion and $10 billion of existing property in California is likely to be underwater by 2050.

The court battle began after a storm in 2016 sent 20 feet of bluffs crashing into the ocean in front of the townhome complex and the owners' request to build a 257-foot concrete seawall was denied by the Coastal Commission. The homeowners association for the Casa Mira townhomes sued, and won, but the commission appealed.

In a tentative ruling in October, the 1st District Court of Appeal in San Francisco agreed with the commission that homes built after the California Coastal Act took effect aren't entitled to permits to build seawalls. Under the landmark Coastal Act, permits were allowed to be issued for seawalls and other armoring to protect “existing structures.”

Since the term was never clearly defined, property owners have tried to argue a different meaning, saying it applies to any building that exists when the permit application is filed.

Attorneys for the commission argue that seawalls and other armoring — which now covers at least 33 percent of the southern California coastline — stop bluffs from eroding and beaches from naturally migrating inland. As sea levels rise, sandy public beaches are sliced thinner than ever.

Surfrider San Diego, which joined the fight against the "seawall precedent" in Half Moon Bay, argued the case could reshape the entire coast.

A final opinion on the seawall case will be issued after a Dec. 11 hearing.

What Threat Does Sea-Level Rise Pose to California?

Introduction

While the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‑19) pandemic and resulting economic impacts have rightly drawn the focus of the Legislature’s and public’s attention since March 2020, other statewide challenges continue to loom on the horizon. Among these are the impending impacts of climate change, including the hazards that rising seas pose to California’s coast. Science has shown that the changing climate will result in a gradual and permanent rise in global sea levels. Given the significant public infrastructure, housing, natural resources, and commerce located along California’s 840 miles of coastline, the certainty of rising seas poses a serious and costly threat.

Strong Case Exists for Including Sea‑Level Rise (SLR) Preparation Activities Among the State’s Priorities. Because the most severe effects of SLR likely will manifest decades in the future, taking actions to address them now may seem less pressing compared to the immediate pandemic‑related challenges currently facing the state. The magnitude of the potential impacts, however, mean that the state cannot afford to indefinitely delay taking steps to prepare. Waiting too long to initiate adaptation efforts likely will make responding effectively more difficult and costly. Planning ahead means coastal adaptation actions can be strategic and phased, helps “buy time” before more extreme responses are needed, provides opportunities to test approaches and learn what works best, and may make overall adaptation efforts more affordable and improve their odds for success. The next decade represents a crucial time period for taking action to prepare for SLR.

This Report Describes Threats Posed by Rising Seas. This report is intended to help the Legislature and the public deepen their knowledge of the threats that California faces from SLR. Developing a thorough understanding of the possible impacts associated with rising seas is an essential first step for the Legislature in determining how to prioritize efforts to help mitigate potential damage and disruption. Moreover, increasing public awareness about the coming threats and the need to address SLR will be an important component in building support for and acceptance of the adaptation steps that should be undertaken.

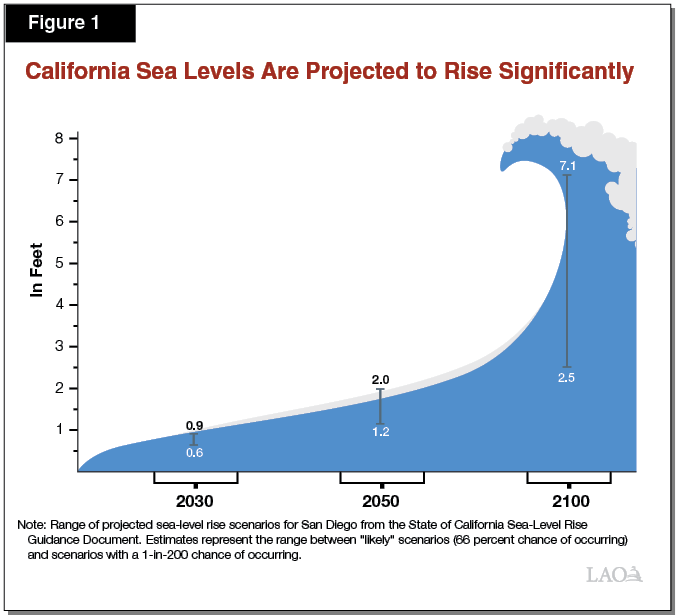

California Will Experience Rising Seas and Tides

Seas Will Rise in Coming Decades. Climate scientists have developed a consensus that one of the effects of a warming planet is that global sea levels will rise. The degree and timing of SLR, however, still is uncertain, and depends in part upon how much global greenhouse gas emissions and temperatures continue to increase. Figure 1 displays recent scientific estimates compiled by the state for how sea levels might rise along the coast of California in the coming decades. (The figure displays data for the San Diego region, but estimates are similar for other areas of the California coast.) As shown, the magnitude of SLR is projected to be about half of one foot in 2030 and as much as seven feet by 2100. These estimates represent the range between how sea levels might rise under two different climate change scenarios. As shown, the range between potential scenarios is greater in 2100, reflecting the increased level of uncertainty about the degree of climate change impacts the planet will experience further in the future.

Storms and Future Climate Impacts Could Raise Water Levels Further. Although they would have substantial impacts, the SLR scenarios displayed in Figure 1 likely understate the increase in water levels that California’s coastal communities will actually experience in the coming decades. This is because climate change is projected to contribute to more frequent and extreme storms, and the estimates shown in Figure 1 do not incorporate periodic increases in sea levels caused by storm surges, exceptionally high “king tides,” or El Niño events. These events could produce notably higher water levels than SLR alone. Moreover, the data displayed in the figure do not include possible extreme scenarios that incorporate the effects of potential ice loss from the West Antarctic Ice Sheet. The likelihood of these severe scenarios occurring is uncertain, but possible. If there is considerable loss in the polar ice sheets, scientists estimate the California coast could experience over ten feet of SLR by 2100.

Rising Seas Threaten the California Coast in Numerous Ways

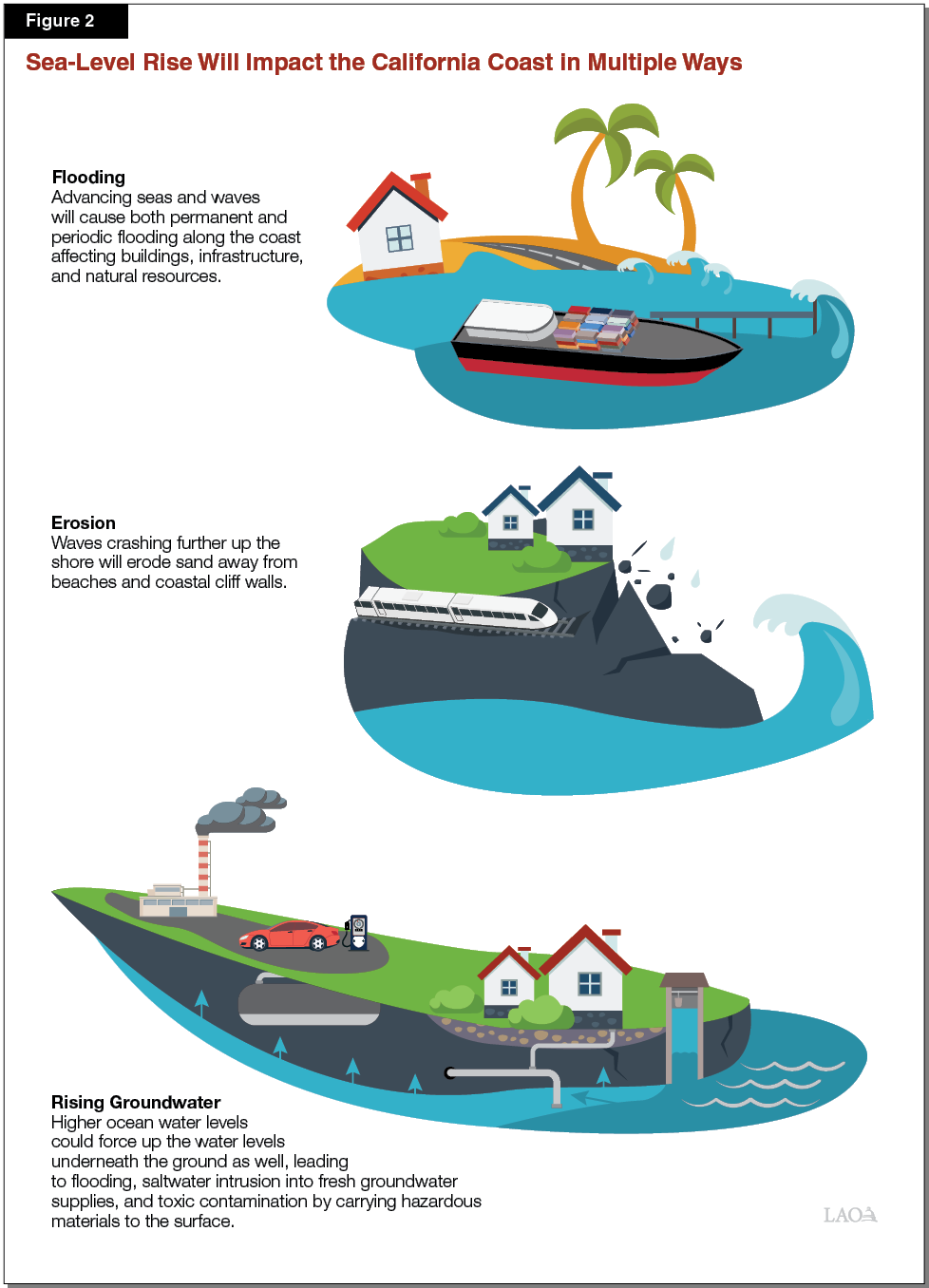

SLR Could Impact Coast Via Flooding, Erosion, and Rising Groundwater. Increased coastal flooding from encroaching seas and waves—in the form of both permanent inundation and episodic events caused by storms—is the most commonly referenced SLR risk. However, rising seas will also trigger other natural processes along California’s coast that could lead to negative impacts, such as erosion and rising groundwater levels. Specifically, waves crashing comparatively further up the shore will erode sand away from coastal cliff walls and beaches. Additionally, in coastal communities where the underground water table is already close to the land surface, higher ocean water levels could also force up the water levels underneath the ground, leading to flooding. For example, one recent study suggested that flooding from emergent groundwater in the San Francisco Bay Area could impact a larger area across the region than wave‑induced flooding. (The state currently is funding an in‑depth assessment of potential coastal groundwater inundation hazards and associated socioeconomic impacts to get a better understanding of associated risks.) Figure 2 illustrates some of these potential impacts.

The natural processes triggered by rising sea levels and coastal storms will affect both human and natural resources along the coast. These impacts have the potential to be both extensive and expensive.

Below, we describe available research regarding how SLR threatens California’s coast in the following seven categories:

- Public infrastructure.

- Private property.

- Vulnerable communities.

- Natural resources.

- Drinking and agricultural water supplies.

- Toxic contamination.

- Economic disruption.

Public Infrastructure

Damage to public infrastructure located along California’s coast represents one of the greatest threats from SLR, as these assets are key components of state and local systems of public health, transportation, and commerce. Examples of publicly owned infrastructure located along the coast include water treatment plants, roads and highways, railways, piers and marinas, and public recreational trails. Depending upon the specific location of these facilities, they could be impacted by both flooding from waves or rising groundwater levels, as well as damage from cliff erosion. In addition, flooding from SLR threatens several important California ports and airports—including those in Long Beach, Los Angeles, San Diego, and Oakland—that are managed by public special districts.

For example, a March 2020 study of SLR vulnerability in the San Francisco Bay Area found that four feet of higher water levels (either from SLR alone or in combination with periodic storm surges) would expose key transportation and commerce infrastructure in the region to flooding. Locations identified as being at risk include: 59 miles of highways and bridges, 48 miles of freight rail lines, 20 miles of passenger rail lines, 11 acres of ferry terminals, 780 acres of seaports, and 4,670 acres of airports. Such flooding could render this important infrastructure unusable for extended periods of time—or, in some cases, permanently—and require costly repairs or modifications.

A different study conducted in 2018 estimated potential impacts from SLR on wastewater infrastructure along the coast. Researchers found that 15 wastewater treatment plants in California will be exposed to flooding with three feet of SLR, growing to 36 facilities with six feet of SLR. Facilities in the San Francisco Bay region are particularly vulnerable, accounting for 30 of those 36 statewide plants, with rising groundwater levels magnifying flood risk. The study also found that with just over three feet of SLR, 28 percent of the plants in the Bay Area region will experience flooding on at least one‑quarter of their surface areas. Flooding of such facilities could cause them to become inoperable for extended periods of time and create a risk of sewage leaks, posing serious threats to public health.

The erosion of coastal cliffs in California is already beginning to cause transportation disruptions. For example, in winter 2019, a portion of railway tracks used to carry passengers between Los Angeles and San Diego had to be closed to repair damage from a bluff collapse near the City of Del Mar.

Private Property

In addition to publicly owned assets, private property is also threatened by the effects of SLR. Specifically, both houses and businesses located along the coast face the threat of increased flooding, and those in cliff‑side locations face damage from eroding bluffs.

A 2015 economic assessment by the Risky Business Project estimated that if current global greenhouse gas emission trends continue, between $8 billion and $10 billion of existing property in California is likely to be underwater by 2050, with an additional $6 billion to $10 billion at risk during high tide. Moreover, a recent study by researchers from the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) estimated that by 2100, roughly six feet of SLR and recurring annual storms could impact over 480,000 California residents (based on 2010 census data) and $119 billion in property value (in 2010 dollars). When adding the potential impacts of a 100‑year storm—a storm with a one‑in‑100 likelihood of occurring in a given year—these estimates increase to 600,000 people and over $150 billion of property value.

Vulnerable Communities

While many coastal communities contain affluent neighborhoods, many of those communities include more vulnerable populations who also face the risk of more frequent flooding and damage from erosion. Those who will be affected include renters (who are less able to prepare their residences for flood events), individuals not proficient in English (who may not be able to access critical information about potential SLR impacts), residents with no vehicle (who may find it more difficult to evacuate), and residents with lower incomes (who have fewer resources upon which to rely to prepare for, respond to, and recover from flood events).

A 2009 study found that flooding from four and a half feet of rising seas combined with a 100‑year storm in California would affect 56,000 people who earn less than $30,000 annually, 45,000 renters, and 4,700 individuals who are linguistically isolated and less likely to understand flood warnings. Additionally, a recent report estimated that four feet of higher water levels would cause daily flooding for nearly 28,000 socially vulnerable residents in the San Francisco Bay Area region. (The researchers defined social vulnerability using a variety of indicators, including income, education level, English proficiency, age, disability status, housing status, citizenship status, and access to vehicles.)

Natural Resources

In addition to buildings and infrastructure, SLR also poses a threat to ecological resources across the state. Flooding has the potential to inundate coastal beaches, dunes, and wetlands. This threatens to impair or eliminate important habitats for fish, plants, marine mammals, and migratory birds. Higher sea levels will also cause salt water to encroach into—thereby degrading—coastal estuaries where fish and wildlife currently depend upon freshwater conditions. A 2018 report by the State Coastal Conservancy and The Nature Conservancy found that 55 percent of California’s existing coastal habitats are highly vulnerable to five feet of SLR, including 60 percent of the state’s iconic beaches, 58 percent of rocky intertidal habitat, 58 percent of marshes, and 55 percent of tidal flats. The researchers estimated that five feet of SLR would also drown 41,000 acres of public conservation lands and add stress to 39 species whose populations have already been classified as rare, threatened, or endangered.

Humans are also dependent on these coastal environments, both for the natural processes that they provide (such as filtering stormwater runoff to improve water quality and providing protection from flooding), as well as their recreational benefits. Millions of California residents visit the coast annually to fish, swim, surf, and enjoy nature, particularly along the one‑third of the coastline owned by the State Park system. The state’s Safeguarding California Plan cites that for every foot of SLR, 50 feet to 100 feet of beach width could be lost. Moreover, a recent scientific study by USGS researchers predicted that under scenarios of three feet to six feet of SLR, up to two‑thirds of Southern California beaches may become completely eroded by 2100.

Drinking and Agricultural Water Supplies

SLR has the potential to impact the fresh water resources upon which Californians depend for drinking, bathing, and growing crops in two primary ways.

First, SLR may cause salty sea water to contaminate certain fresh groundwater supplies. Some coastal regions of the state are heavily dependent on drawing fresh water from underground aquifers to support their population and to grow crops. As illustrated in Figure 2, in some areas rising sea levels are likely to push saltwater up into these groundwater basins, thereby degrading key fresh water resources. The degree of this risk is still unknown and being researched, and will vary across the state based on factors like local geology and hydrology. Additionally, SLR may exacerbate conditions for coastal fresh water aquifers that already are experiencing some degree of saltwater intrusion due primarily to their current pumping practices—including in the Pajaro and Salinas Valleys, the Oxnard Plain, and certain areas in Los Angeles and Orange Counties.

Second, SLR could impair one of the state’s key water conveyance systems. The State Water Project brings fresh water supplies to 27 million people and to irrigate 750,000 acres of farmland. The system is highly dependent on the integrity of the levees in the Sacramento‑San Joaquin Delta to successfully move this water from the northern to the central and southern parts of the state. Higher sea levels pushing into the Delta from the ocean through the San Francisco Bay, however, will place more pressure on those levees. Should the levees in the southern part of the Delta be damaged and breached by these higher water levels, it would cause salt water to flood further into the estuary. This could contaminate the fresh river water supplies that currently pass through the Delta into the State Water Project’s pumps and canals. Additionally, even if levees remain undamaged, SLR will on the natural bring salty tides further into the Delta estuary. This will require the state to direct greater flows of fresh river water to “push back” on those tides in order keep saltwater away from the conveyance pumps located at the southern end of the Delta. Research suggests that such conditions would therefore likely decrease the amount of freshwater supplies available for exporting via the State Water Project.

Toxic Contamination

Flooding and rising groundwater levels caused by SLR could also threaten public health by exposing coastal residents to toxic contamination. Specifically, in areas where underground sea water pushes the water table up towards—or above—the ground surface, water could also damage and intrude into underground sewer pipes and systems. This could lead to more prevalent incidents—particularly during high tides and storms—of raw sewage seeping into fresh groundwater aquifers or backing up into streets and homes. Additionally, water infiltrating upward may flow through hazardous contaminants currently buried in the soil and carry them toward the surface, thereby distributing pollutants into fresh groundwater supplies and surface soils, as well into stormwater runoff that flows through local streets and fields. Contaminated lands located along the coast and bay at risk of both surface and groundwater flooding include active and closed landfills, as well as “brownfields” which are undergoing or require cleanup—such as federal Superfund sites, military cleanup sites, and California Department of Toxic Substances Control sites. Flooding from SLR could also lead to toxic contamination from facilities that generate and store hazardous materials, such as laboratories, manufacturing facilities, and gas stations. Floodwaters could penetrate both surface‑level and underground tanks and force out toxic liquids, or liberate waste from pits or piles.

Available research suggests the threat of SLR causing harmful contamination is significant. For example, research suggests that more than 330 facilities across California that contain hazardous materials and are being regulated by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency are at risk of flooding with 1.4 meters (about five feet) of SLR combined with a 100‑year storm. Additionally, a study undertaken in Contra Costa County found that 28 brownfield sites within the county are at risk of flooding with two feet of SLR combined with a 100‑year flood, growing to 38 sites with six feet of SLR. (The study did not consider the potential compounding impacts of groundwater flooding.) These sites contain 68 different contaminants of concern, including various metals, corrosive materials, petroleum products, volatile organics, and pesticides. The study found that “these contaminants can potentially affect soil, sediments, sediment vapor, groundwater, or surface water.”

Economic Disruption

The potential impacts of SLR could have negative impacts on the economy and tax base—both locally and statewide—if significant damage occurs to certain key coastal infrastructure and other assets. For example, according to California’s Fourth Climate Change Assessment, the state’s ports were the destination for $350 billion in goods imported to the U.S. in 2016—by far the largest of any state. This economic activity would be disrupted by flooding of the docks, surrounding roadways, or adjacent railways through which goods are distributed. The productivity of the state’s workforce—and associated economic output—would also be affected by SLR. For example, a recent study found that over 104,000 existing jobs in the San Francisco Bay Area—including from some of the highly successful technology companies located along the Bay’s shore—would need to relocate or be lost under a scenario of four feet of flooding in the region.

Moreover, the potential erosion of beaches associated with SLR would impact not only Californians’ access to and enjoyment of key public resources, but also beach‑dependent local economies. For example, research on the potential economic impacts of SLR specific to the San Diego region found that the tourism and recreation industries face the greatest vulnerabilities. Overall, the study found that about three feet of SLR combined with a 100‑year storm would pose a threat to 830 business establishments in San Diego County, which could in turn affect 15,000 jobs, $2 billion in property sales, and $2 billion in regional gross domestic product. A scenario of six feet of SLR combined with a 100‑year storm increases the scope of this vulnerability to over 2,600 business establishments, which would affect 49,000 jobs, $8 billion in sales, and $6.1 billion of the county’s gross domestic product.

Additionally, if property values fall considerably from the increased risk and frequency of coastal flooding, over time this will affect the annual revenues upon which local governments depend. To the degree local property tax revenues drop, this also could affect the state budget in some years because the California Constitution could require that losses in certain local property tax revenues used to support local schools be backfilled by the state’s General Fund.

Conclusion

Coastal Adaptation Activities Can Help Lessen SLR Impacts. While the risks California faces from SLR are great, the state and local governments can take steps to prepare for and help mitigate against potential impacts. The state, coastal communities, and private property owners essentially have three categories of strategies for responding to the threat that SLR poses to assets such as buildings, other infrastructure, beaches, and wetlands. Specifically, they can (1) protect, by building hard or soft barriers to try to stop or buffer the encroaching water and keep the assets from flooding; (2) accommodate, by modifying the assets so that they can manage regular or periodic flooding; or (3) relocate, by moving assets from the potential flood zone to higher ground or further inland.

State Can Play Key Role in Supporting Local Adaptation Efforts. Although much of the work to prepare for the impacts of SLR needs to take place at the local level, the state can help. For example, the state can take steps to help (1) foster regional‑scale collaboration; (2) support local planning and adaption projects; (3) provide information, assistance, and support; and (4) enhance public awareness of SLR risks and impacts. Please see our December 2019 report, Preparing for Rising Seas: How the State Can Help Support Local Coastal Adaptation Efforts for more discussion of how the Legislature can support local governments in their SLR preparation efforts.

Certain SLR Preparation Efforts Can Be Undertaken Despite More Limited Fiscal Resources. The recent COVID‑19 pandemic and economic downturn complicate SLR preparation efforts, as fiscal resources are more limited at both the state and local levels. However, the state and local governments can undertake some essential near‑term preparation activities—such as planning, establishing relationships and forums for regional coordination, and sharing information—with relatively minor upfront investments. For example, neighboring local governments and stakeholder groups could form regional climate adaptation collaborative groups to coordinate how to respond to cross‑jurisdictional climate impacts, create efficiencies and economies of scale, and build capacity through shared learning and pooling of resources. The San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission has begun organizing one such effort in the Bay Area region, through its Bay Adapt regional strategy initiative. Our report, Preparing for Rising Seas, discusses how the state could help facilitate such collaborations, along with other recommendations for how to make progress in mitigating the risks posed by SLR. Given the pending significant risks posed by SLR in the coming decades—and the additional public safety and economic disruptions that will result absent steps to mitigate potential impacts—the state and its coastal communities cannot afford to defer all preparation efforts until economic conditions have fully rebounded from the recent crisis. The magnitude of the risks described in this report highlight the importance of California including SLR preparation activities among its many pressing priorities.

Homes vs. beaches: Court makes key decision in battle over California seawall construction amid ocean rise

In

a case that could affect thousands of property owners and beaches

visited by millions of people along California’s 1,100-mile coastline, a

state appeals court has indicated it will uphold rules limiting the

construction of sea walls along the coast.

In

a case that could affect thousands of property owners and beaches

visited by millions of people along California’s 1,100-mile coastline, a

state appeals court has indicated it will uphold rules limiting the

construction of sea walls along the coast.

The case, centered on the California Coastal Commission’s decision to deny a sea wall for 10 vulnerable townhouses near Half Moon Bay, is playing out at the First District Court of Appeal in San Francisco. It has been closely watched by environmental groups, builders and oceanfront cities across the state as sea levels continue to rise due to climate change, putting billions of dollars of property at risk.

“It’s a big deal,” said Charles Lester, director of the Ocean and Coastal Policy Center at UC Santa Barbara. “This will potentially resolve a question that’s been under debate for years now.”

In late October, the appeals court issued a tentative opinion agreeing with the Coastal Commission that buildings constructed after Jan. 1, 1977, are not entitled to obtain permits to build sea walls.

The state’s landmark Coastal Act took effect on that date. It says the commission “shall” issue permits for sea walls and other types of armoring to protect “existing structures” against erosion from battering waves.

But state lawmakers never clearly defined the term. Property owners have argued “existing structures” means any building present at the time the permit application is filed. But the Coastal Commission’s attorneys have argued in recent years that “existing structures” only means those built before 1977.

They cite a growing body of scientific evidence that shows that construction of concrete walls along the coast stops bluffs from eroding, depriving public beaches of sand. Such armoring also stops beaches from naturally migrating inland, resulting in them becoming submerged over time.

“Sea level rise is a new game in town,” said Lester, the former executive director of the Coastal Commission from 2011 to 2016. “The shoreline is moving landward. We’re looking at projections of losing a significant amount of California’s beaches due to sea level rise. And most of that is in places that have a lot of sea walls.”

The court scheduled a Dec. 11 hearing and then will issue a final opinion. In its tentative opinion, the judges cited earlier versions of the Coastal Act as it was being debated in the state Legislature, and showed how broad language allowing sea walls was tightened to read “existing structures.”

“If the Legislature intended to guarantee any structure shoreline protection — regardless of when it was constructed — it could have retained the broad language,” the appeals court wrote.

Private property rights groups are unhappy.

“There may not be a simple solution. But reinterpreting the Coastal Act to sacrifice the rights of coastal landowners isn’t the way to solve these problems,” said Jeremy Talcott, an attorney with the Pacific Legal Foundation, a Sacramento property rights group. “Simply allowing thousands of homes to fall into the sea is a very drastic decision.”

The case will decide the fate of a quiet neighborhood on the San Mateo County coast.

In 2016, a severe storm caused 20 feet of bluffs to collapse into the ocean in front of Casa Mira, a complex of 10 townhouses on Mirada Road that’s 2 miles north of Half Moon Bay. Worried their homes were in imminent danger, the owners obtained an emergency permit from the Coastal Commission to place boulders, called riprap, along the crumbling shoreline to block the waves from causing more damage.

But when they applied to build a permanent 257-foot concrete sea wall, the commission said no.

“Sea walls eat away at the beach,” said the commission’s chairwoman, Dayna Bochco, during the 2019 meeting. “So someday as this keeps moving in and in, you are going to lose that beach if you have that sea wall. I think it’s anti-access.”

The commissioners voted to allow only 50 feet of sea wall to be constructed in front of an adjacent four-unit apartment building that was built in 1972. They said the Casa Mira, whose townhouses were built in 1984, couldn’t have a sea wall.

The Casa Mira Homeowners Association owners sued and won in San Mateo County Superior Court last year. The Coastal Commission appealed.

In its tentative opinion, the appeals court overturned much of the lower court ruling, siding with the Coastal Commission and its Jan. 1, 1977, cutoff date.

The appeals court said the Casa Mira homeowners still can get the sea wall they want, however. But only because it would protect a portion of the California Coastal Trail that runs between their homes and the public beach below, making it a “coastal dependent” use to improve public access that is allowed protection under the Coastal Act.

Joshua Emerson Smith, a Coastal Commission spokesman, said the agency will withhold comment until the appeals court issues its final ruling. Thomas Roth, a San Mateo attorney who represents the Casa Mira Homeowners Association, did not respond to requests for comment.

With so much at stake, experts say the issue could end up at the state Supreme Court next year. For that to happen, one of the parties would have to appeal, and the court would have to agree to take the case.

Numerous groups filed briefs in the case, including the Surfrider Foundation, the Bay Area Council and the California Building Industry Association.

“This is not just a California problem,” Lester said. “There are houses falling into the ocean in North Carolina, in Hawaii and other places. We’re not going to stop the ocean from rising. The question is what do we choose to protect over the long run? What’s in the public interest? Some of these developments have arguably reached the ends of their natural lives if you want to protect the beaches.”

Originally Published:

California Trial Court Clarifies When Coastal Property Owners Are Entitled to Seawall Protection Under the Coastal Act

In a recent California trial court decision, Casa Mira Homeowners Association v. California Coastal Commission (Casa Mira), the court added another significant page in the decades-long debate over which coastal properties are entitled to shoreline protective structures from the assumed effects of coastal erosion. While a California statute–Public Resources Code Section 30235–provides for the clear, mandatory protection for certain properties as long as they are “existing structures,” the temporal determination of when structures are considered “existing” has been the subject of much debate.

As explained below, the San Mateo County Superior Court in Casa Mira recently ruled the California Coastal Commission’s (Commission) proverbial line in the sand over whose property is entitled to protection was unreasonable and failed to properly balance the consideration between beach access and private property rights. The court stated the Commission’s position that “all structures along the coast that become endangered or unstable due to erosion should be allowed to collapse” is unreasonable and “contrary to the stated purpose of the Coastal Act.” Instead, the court ruled “it is clear that the [Coastal Act] supports people protecting their existing structures from the danger of property damage due to subsequent erosion.”

The case largely turned on the statutory interpretation of a provision of the Coastal Act (Pub. Resources Code, section 30000 et seq.). The Coastal Act, which went into effect on January 1, 1977, provides a set of coastal policies to guide land use decisions along the California coast, and established the Commission to oversee and implement the Act along the majority of California’s coast. One of the most contested and litigated issues under the Coastal Act has been the Commission’s denial of CDPs for seawalls or revetments. These are shoreline protective devices that generally run parallel to the shoreline and are designed to protect structures, habitat or other human activity from coastal erosion. As relevant here, the Commission maintains exclusive jurisdiction over CDPs for shoreline protective devices located seaward of the mean high tide line. Section 30235 of the Coastal Act states that revetments, seawalls and other shoreline protective devices “shall be permitted when required to serve coastal-dependent uses or to protect existing structures or public beaches in danger from erosion and when designed to eliminate or mitigate adverse impacts on local shoreline sand supply.” (Emphasis added.) Most of the debate over the foregoing provision has been over whether the term “existing structures” means structures existing at the time of the seawall CDP application or is limited to structures that existed before the adoption of the Coastal Act on January 1, 1977.

The consequences for this interpretive dispute can be drastic for coastal property owners who require shoreline protection for the existing structures on their properties. The Commission’s current interpretation of “existing structures” would foreclose approval of CDPs for seawalls for buildings built after January 1, 1977, leaving them unprotected. For the first 38 years of the Coastal Act, however, the Commission consistently interpreted “existing structures” as being those that were in existence at the time the Commission acted on a CDP application.

While the Commission maintained that interpretation of Section 30235 for almost four decades, in 2015 the Commission pivoted to a more restrictive definition. In its 2015 Sea Level Policy Guidance (“2015 Guidance”), the Commission stated going forward, it would maintain that “structures built after 1976 pursuant to a [CDP] are not ‘existing.’” (Sea Level Policy Guidance, at p. 166.) Since the release of the 2015 Guidance, the Commission has held fast to the guidance and used its new interpretation of Section 30235 as a basis to deny CDP applications for seawalls. In July of this year, the issue of the proper interpretation of “existing structures” came to a head again in Casa Mira, where the trial court ruled the Commission’s restrictive interpretation was improper.

In Casa Mira, the homeowners association applied for a CDP to construct a 257-foot seawall to protect a collapsing bluff that threatened ten townhomes, an apartment building, a sewer line and a section of the California Coastal Trail. In 2016, the Commission granted an emergency CDP for Casa Mira for a rip-rap (rock pile) revetment in response to erosion from a severe winter storm, and then followed up with a regular application for a CDP to build a permanent concrete seawall. The Commission determined only the apartment building and Coastal Trail were entitled to seawall protection and thus it approved only a 50-foot section of the seawall, but denied the rest of the sought after shoreline protection. The Commission reasoned because the Casa Mira townhomes and sewer line were not built until 1984, they were not considered “existing structures” entitled to the seemingly mandatory seawall protection provided in Coastal Act section 30235.

Casa Mira argued the Commission’s limited “approval” of the 50-foot seawall amounted to an effective denial of its CDP application because it would leave the townhomes and sewer line without protection. It contended the proper interpretation of the term “existing” in section 30235 is “existing at the time of the CDP application,” and thus, Casa Mira was entitled to approval of its CDP for the 257-foot seawall.

In contrast, the Commission argued the mandate to approve CDPs for “existing structures” only applied to those structures that were existing prior to 1976. Because the language of section 30235 does not specifically define what “existing” means, the Commission argued its agency interpretation should be granted deference by the court. Even if the court limited its review to the plain language of the statue, the Commission contended “existing” should be interpreted as existing “at the time the word was used,” in the statute—1977.

Addressing the parties’ arguments, the court determined the language of section 30235 was unambiguous, and thus, the disputed term—“existing structures”—must be interpreted in its “ordinary, general, common sense meaning.” Under such an ordinary interpretation, the court ruled “it is clear that the statute supports people protecting their existing structures from the danger of property damage due to erosion.” The court stated the Commission’s interpretation that would effectively mandate a policy of allowing all sea-side homes and buildings built after 1976 to fall into the ocean was “unreasonable” and contrary to the Coastal Act’s purpose.

While the court’s holding is limited to its conclusion that existing under section 30235 means existing as of the time of the application, the court did also address various additional aspects of the parties’ arguments. First, the court ruled even if the statute was ambiguous, there is no legislative history available to support the Commission’s restrictive interpretation. The court reminded the Commission that on this legal issue, the court, not the agency, had the final say on the statute’s interpretation. Second, the court recognized a different Coastal Act provision, section 30253, prevents new development that would require a seawall to be built at the same time as the house. However, it pointed out in contrast to section 30253, Coastal Act Section 30235 applies only to existing development. If a structure has already been permitted and developed and then later erosion necessitates the need for a shoreline protection, then, absent a waiver of future shoreline protection, Section 30235 would allow such seawall construction. The court emphasized the Commission’s interpretation of “existing structures” as only applying to pre-1977 seawalls amounted to an unbalanced consideration of value of creating sandy beach without weighing and considering the “protection and enjoyment of nature and enjoyment of private property.”

The Commission has authorized an appeal of the decision in Casa Mira. The ultimate resolution of this issue, either by the Court of Appeal, or possibly, the California Supreme Court, will be very consequential to coastal homeowners whose existing homes are threatened by coastal erosion and in need of the shoreline protection that section 30235, by its terms, seemingly guarantees.

Comments

Post a Comment